Hi! Sorry!

I so enjoy writing these best-of posts, but this one is now a month late. Why? Thankfully, it’s for good reasons. I’m just busy. I’m working full-time as an educator, am preparing my next directorial projects, and am almost constantly surrounded by friends and loved ones. 2024 was a most marked improvement over 2023, which in hindsight seems only a more and more dreary and lonesome year.

But 2024 was great. I took on my first-ever work in literary publishing (see if you can find any familiar names next time you visit the finer newsstands), directed Shakespeare after a decade of merely performing Shakespeare (more about that in the All’s Well That Ends Well section of my directing page), returned to film acting after a long absence, made all sorts of new friends wherever I went… yes, you won’t hear me complaining! In the past, I’ve longed for my “real life” to begin, as if all of the daily annoyances and iniquities which risk turning our lives into ponderous drudgery had rendered mine into an effective half-life. Now, I can say with contentment that my real life has begun.

But this post is already overdue and overlong, so I won’t keep you. My best of 2024 list is below–and, as usual, it’s a list of all the best stuff I heard, read, and saw, regardless of what year it originally came out.

MUSIC

James Ferraro — Last American Hero (2008) / Night Dolls With Hairspray (2010) / Skid Row (2015)

An indie rock subgenre called “hypnagogic pop” was one of the sounds du jour in the 2010s, but none of its associated artists accessed hypnagogia (the state of consciousness between sleep and wakefulness, crucial to understanding the fields of psychedelia and psychoanalysis) better than James Ferraro. I spent the latter half of 2024 discovering album after album of Ferraro’s surrealistic, psychic worlds, some almost entirely bereft of images and words, but each conjuring eerily familiar interior landscapes which often veered into the frightening and uncanny. Listen to one of his longform compositions like Last American Hero, and before you know it, its chintzy, twangy guitar loop and stuttering, lo-fi synth bed bring to mind manifold iconography of American media, consumerism, and conformity–associations which would please Ferraro, who scream-writes in the album’s liner notes of “A GROUP OF HUMANS PRESUMED LOST FOR THE LAST DECADE AND A HALF FOUND ALIVE CAMPING OUT IN THE BACK RECESSES OF A COSTCO SUPER MARKET” and other such nightmares of our national sicknesses.

Yet even in a more traditionally lyrical-narrative mode, Ferraro formulates monuments of breathtaking dream logic which access intimate themes of sex, society, race, and abuse: the adolescent narrator of “Leather High School,” like a colorful and poisonous frog, cheerfully narrates a twisted version of the teen sitcom where the barriers of child and adult, of consent and abuse, have been completely erased; then, there’s “Doctor Hollywood,” in which Ferraro, a biracial man, croons in a midnight-cold, high and fragile register the unshakeable hook:

“Can you change my fate?

Fix the race?

Set me up with a brand new face?

Yeah, Doctor Hollywood”

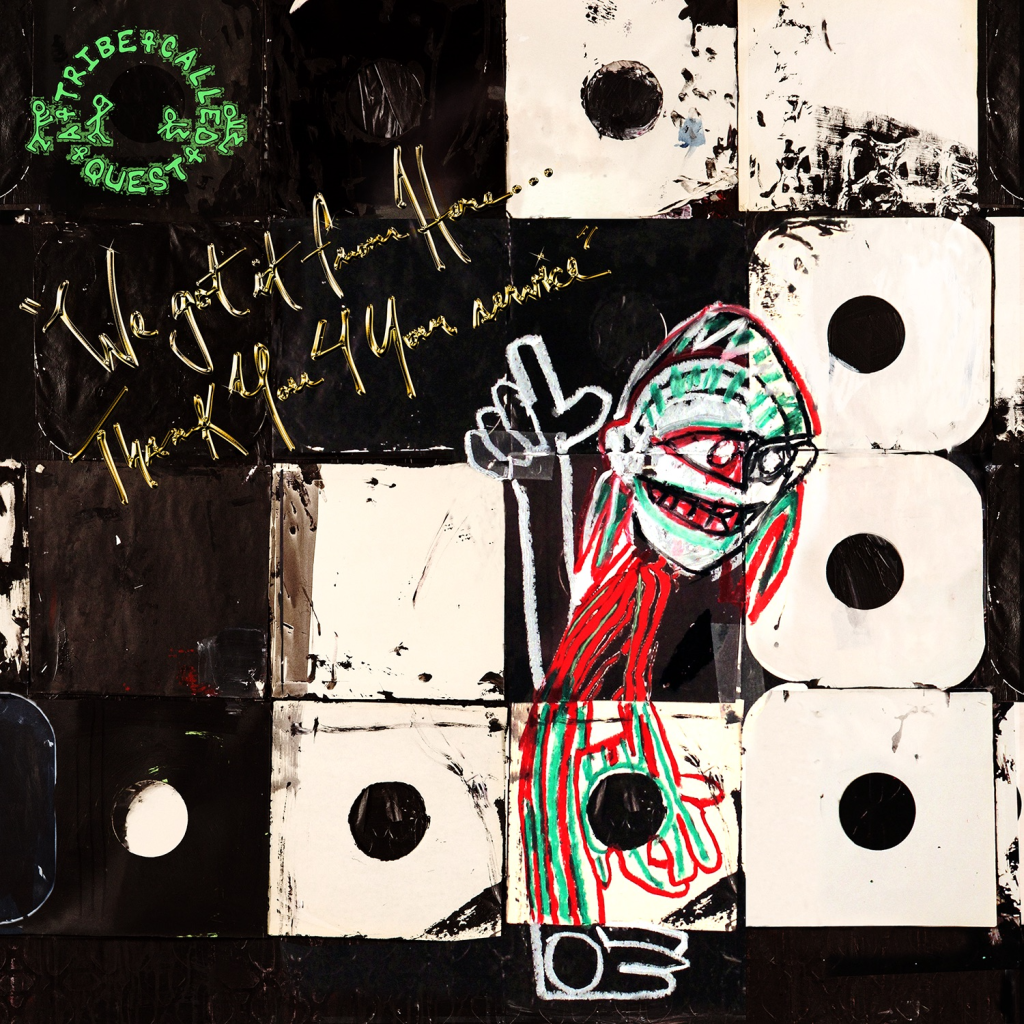

A Tribe Called Quest — Thank You For Your Service… We Got it From Here (2016)

While A Tribe Called Quest was making this album, founding member Phife Dawg died. What did they do? They addressed it, and interwove their loss into the very fabric of the work.

They included moving eulogies for Phife, such as in “Black Spasmodic,” in which Q-Tip follows up a Phife verse with a guess as to what his vertically-challenged friend would’ve said next. Perhaps it would’ve been: “I’m leaving, but nigga, you still got the work to do / I expect the best from you, I’m watching from my heaven view / Don’t disappoint me, make sure that they anoint me / As the blue ribbon pedigree, the best of show, five-foot-three.”

They also called in support to fill Phife’s shoes, including Busta Rhymes, doing the best work of his career and in full communication with his Jamaican roots. He toasts on songs like “The Donald,” and though the title refers to “Don Juice,” one of Phife’s many nicknames, in 2016 it must’ve had an ominous significance. Goodbye to one Don, hello to another.

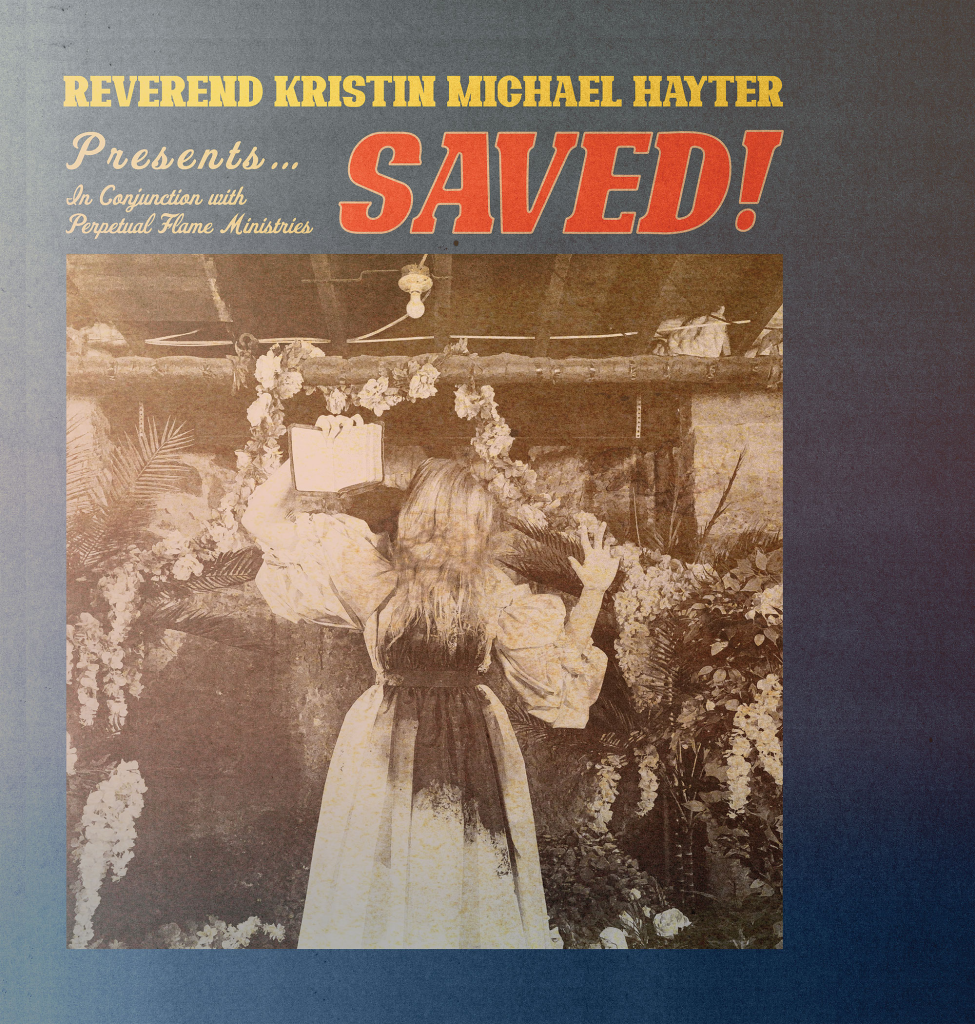

Reverend Kristin Michael Hayter — Saved! (2023)

Saved! is Kristin Hayter’s terrifying, immersive exploration of Southern Baptist music. Definitive covers, landmark originals. Veneration of Christ’s blood and thirst for the blood of vanquished lovers become one in this cryptic album’s closed-circuit world. I didn’t realize that nearly every sound on this album (echoes, jingling, warbling, scratching, buzzing, tongues and ululation) was produced by voice or prepared piano until I saw her perform it live in January. It’s possible to get lost in this fiendish, ancient place.

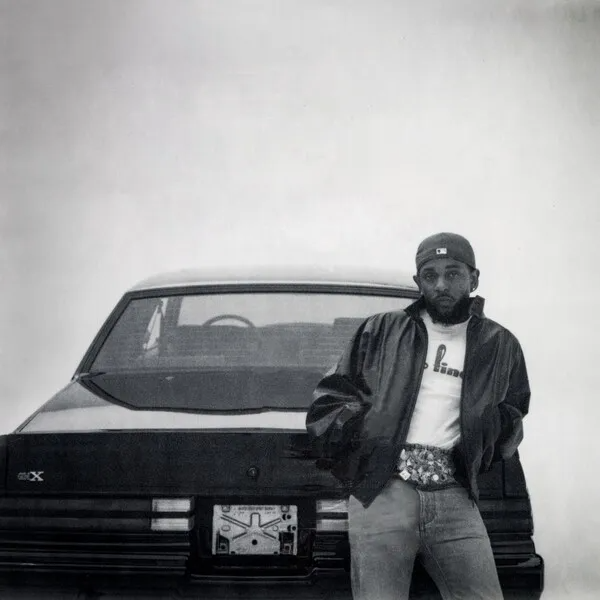

Kendrick Lamar — Singles (2024)

In 2024 Kendrick sheared himself of the pious moralizing and the bloated, soul muzak backdrops that have in the past prevented me from fully getting on board with him. What was left was something raw, mean, and gripping.

“Euphoria” is a long, meandering, yet endlessly infectious peal of trash talk, and, importantly, it’s weird in the way the pop star subject of its ire never could be. It begins with nearly two minutes of Kendrick making noises of gunfire and rapping in a high, wobbly falsetto, reminiscent of the similar “depleted old man” voice Tom Waits sometimes employs on songs like “Dirt In The Ground.”

Kendrick goes down routes few others would’ve thought to take. He seems to channel Dr. Seuss in one section of “Euphoria” (“I like Drake with the melodies, I don’t like Drake when he act tough”) and later in the same song spends significant time working within an extended Haley Joel Osment metaphor (or “Joe Hale Osteen,” as Kendrick malaprops in a bit of himbo playfulness)

“Not Like Us,” though the bigger megahit, brings some of the same idiosyncrasies. In the first line of the song Kendrick references an internet meme from 2010 and basketball player John Stockton, the whitebread star of the Utah Jazz from the 80s and 90s.

But these songs wouldn’t amount to much if they were just weird; they gain their power by being weird and righteously angry. When Kendrick fumes “I hate the way that you walk, the way that you talk, I hate the way that you dress,” one gets the impression he’s raging not only against the entitled Drake’s many abuses of power, but also the smug mediocrity and poverty of vision that Drake has exerted over mainstream culture for nearly two decades. It’s time for the weirdos to take control. I can’t remember the last time zeitgeistian music of the moment was this virtuosic, eccentric, and thrilling.

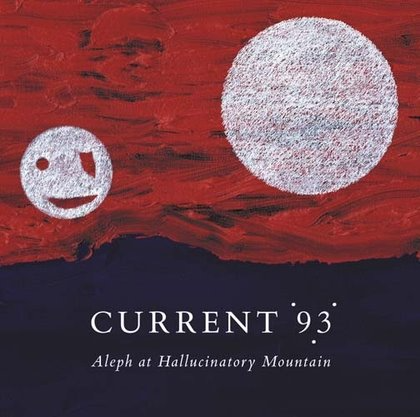

Current 93 — Aleph at Hallucinatory Mountain (2009)

David Tibet’s “apocalyptic folk” project Current 93 has been around since the early 80s, and though his usual artistic mode is that of hissed surrealist poetry over a bed of spartan English folk accompaniment, he has dabbled with electric psychedelia before on songs like Horsey and Hitler As Kalki. However, this rather underlooked, late-career Current 93 suite feels like the culmination of those atavistic impulses. Folk and rock musicians seemed drawn to Tibet for this monolithic work: English guitarist James Blackwell contributes fingerplucked compositions as pure and smooth as flowing water, folk-rocker Alex Neilsen (of the great Glasgow band Trembling Bells) strikes the drum, and the legendary Rickie Lee Jones even shows up to add a pane of vocal longing to one track. Listening to the ten-minute-long “Not Because the Fox Barks,” it’s easy to imagine that Tibet had unlocked something here.

Honorable mentions: Ton Steine Scherben – Warum geht es mir so dreckig? (1971), When — Drowning But Learning (1987), Ghostface Killah — Fishscale (2006), Ulver — The Norwegian National Opera (2012)

The Savage God: A Study of Suicide by Al Alvarez

In the spring of this year I was very briefly in talks to bring educational theatre programming to New York City prisons. The task demanded of me was enormous: I was to devise a show for the inmates to perform which would reflect meaningfully on the subject of suicide, since suicide, as I was informed, “had recently become relevant to their lives.” I babbled on the Zoom call (“yes, I’ll do it, for what is “To be or not be to,” the most famous speech in the theatrical canon, but a discourse on suicide,” etc.) until my prospective employer cut me off, rushing off to his next meeting and trusting me to present a proposal within a week. My camera shut off, I was alone again in my room, and I was faced with the uncomfortable reality that I was empty of ideas, save for one: I would go to the Strand and get a copy Al Alvarez’s The Savage God: A Study of Suicide.

The Savage God is Alvarez’s meticulously researched, vividly interdisciplinary survey of suicide’s presence in Western culture. Professorial in the most 1960s way possible (enamored of the Western poetical canon, but with just the most minor flanges of the rebellious; an artist and poet himself, but a mostly unsuccessful one, and a grumbler therefore), Alvarez begins the book with a 40-page account of his friendship with Sylvia Plath before zooming out into a survey of literary history.

John Donne, a favorite subject of Alvarez’s, gets a large portion of the limelight. For Donne, suicide seemed a constant temptation until the moment of his natural death. Donne wrote Biathanatos, his defense of suicide, when he was 36 years old. He was professionally obscure, cloistered in a country home in Surrey, surrounded by his wife and countless children, “ill and poor and child-ridden” (Alvarez’s genius phrase). To this unhappy man, impotent in one way and all too potent in another, suicide seemed the only way of reclaiming his identity and freedom to choose. Yet even in Donne’s less polemical work there is a sense that he’s been rejected, and a yearning to be released:

“But I am None; nor will my Sunne renew.

You lovers, for whose sake, the lesser Sunne

At this time to the Goat is runne

To fetch new lust, and give it you,

Enjoy your summer all.”

Alvarez attempted suicide just nine years before the publication of The Savage God, and he ends his book with his account of the event. Alvarez’s attitude towards suicide is not gothic or romantic; he despises what he put his wife and children through, on Christmas Day no less, and ascribes the act to foolishness and immaturity: “blame it, perhaps, on my delayed adolescence.” In the end, Alvarez’s assessment of suicide is not moralistic, but rather sociological and individual, cognizant of life’s pain and iniquity, sympathetic to the suicides themselves, but ultimately aware of the work to be done here on earth:

“It seems to me […] a terrible but utterly natural response to the strained, narrow, unnatural necessities we sometimes create for ourselves. And it is not for me.”

You probably saw this coming, but I declined the contract with the Department of Corrections. It was above my paygrade, and besides, the entire time I should’ve been thinking about the show I was thinking with Alvarez instead.

Master of Reality by John Darnielle

John Darnielle’s debut in long-form fiction can be found in an unlikely place—as the 56th installment of the beloved 33⅓ series of music criticism books. Darnielle, characteristically subverting the form, did not choose to launch an appraisal Black Sabbath’s 1971 heavy metal classic Master of Reality, but instead introduced us to Roger Painter, a teenage boy institutionalized in a youth psychiatric center in 1985. In the journal he’s mandated to keep as part of his treatment, Roger swears, spits, and pleads for his confiscated Walkman and Sabbath tapes to be returned to him. He begins to unfold the book you half-suspect; song by song, he attempts to convince the ward staff of Sabbath’s artistic value and social worthiness. But then, his journal suddenly ends.

We rejoin Roger years later. He is an adult, and an unhappy one. He works as a butcher in a grocery store. He hates himself, and he wonders where it all went wrong. So, in an attempt to resolve his mystery of the self, he finishes the journal. Not only does he return to Sabbath as a man, letting it transport him back to the days of his dazzled and chaotic youth, but he has his final say with the youth psychiatrist, whose fickle neglect and lazy disregard set Roger up for an adulthood of social quarantine and unequal opportunity.

I finished reading this short book one May evening on a stool at the Lucky 13 Saloon, a heavy metal bar in Gowanus. As an adult who still struggles with the scars of being institutionalized as a kid, it spoke to me in ways that few works of art ever have, and in ways I still have yet to understand.

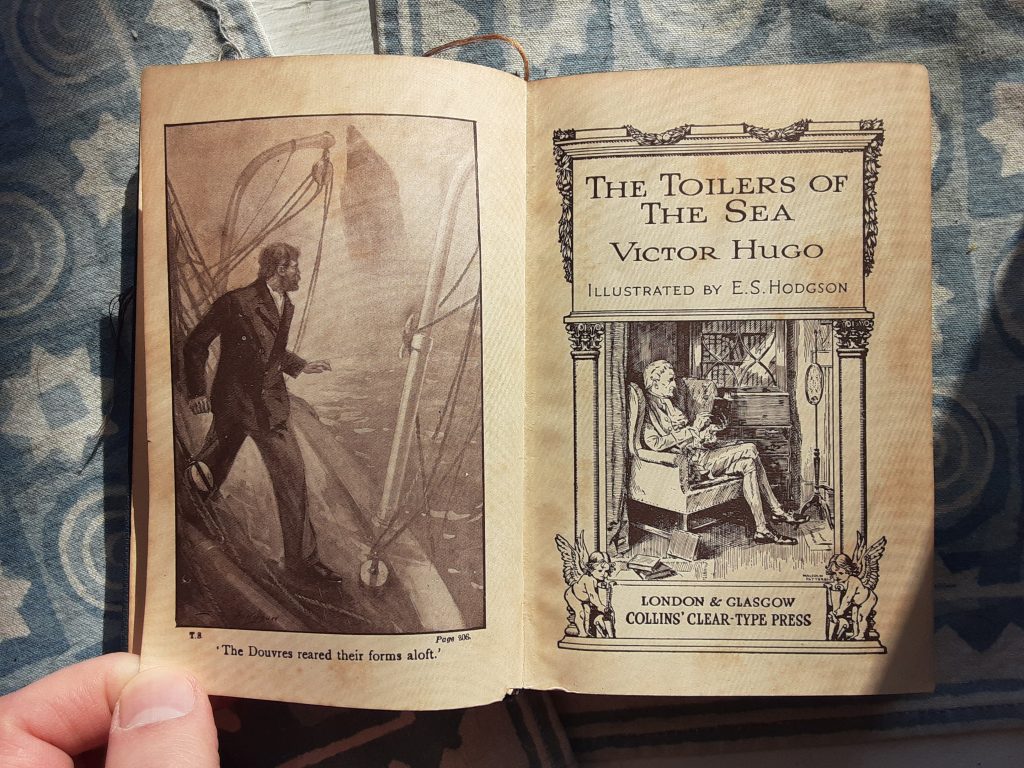

The Toilers of the Sea by Victor Hugo

A scant few years after the encyclopedic Les Misérables, Hugo wrote The Toilers of the Sea, a book which, in many ways, seems to have been intended as Les Misérables‘s complete opposite. Where Les Misérables features a cast of characters the size of a small city, The Toilers of the Sea has very few characters indeed, and only one of them is explored in any real detail. That character is the stoic Gilliatt, who lives alone in a kind of masculine solitude upon a tiny, shabby island in the English Channel. He is called by his neighbors “malicious,” but if there is, in fact, much bad or evil about him, it is merely his aloofness and his secrecy, which others have grown to distrust and beware; they even suspect him to be a witch.

It is the dramatic conflict between violent nature and irrepressible man that makes up the most challenging and unique material in this novel. Nearly half the length of The Toilers of the Sea deals with a single man, alone, in a single setting comprising a space no larger than the stairwell of an apartment building. It describes the tense and excruciating process of Gilliatt’s attempt to rescue a steamship’s engine from a maritime wreck, with tools barely more sophisticated than his own two hands. His labors are immense, and his deprivations are sobering to reflect upon.

“He felt himself the enemy of an unseen combination. […] He suffered from heats and shiverings. The fire ate into his flesh; the water froze him; feverish thirst tormented him; the wind tore his clothing; hunger undermined the organs of the body. […] He had a constant sense of something working against him, of a hostile form ever present, ever labouring to circumvent and to subdue him. […] The invisible persecutor was destroying him by slow degrees. Every day the oppression became greater, as if a mysterious screw had received another turn.”

I read this book in a beautiful clothbound edition with illustrations by E. S. Hodgson.

Saint Joan of Arc by Vita Sackville-West

Sackville-West wrote this clear-eyed biography of Joan of Arc in 1936, not so very long after George Bernard Shaw’s play on the same subject, and they seemed to come to their respective Joan books with similar artistic goals: after centuries of mythologies around Joan, after the Romantics (Schiller, Rossetti, et al) took her up as a cause célèbre, and after her canonization in 1920, was it possible to render her in art, not as angel-warrior-child, but as a real human being? So, dipping fastidiously into her largely French sources, Sackville-West weaves an expansive tapestry of Joan’s life and times–full of facts, yes, but also dotted with crackpot theories (Sackville-West hypothesizes that Joan and her father shared a telepathic link), uber-Anglo cattiness (“Charles VII could not help being born a backboneless creature…”) and medieval narrative flavors that bring to mind Woolf’s adventures in historical fiction (“They set forth in no very favorable conditions. The rains that winter had been exceptionally heavy, and the rivers were overflowing their banks. The Duke of Bar himself had to forgo the fish on his table, by reason of the floods. It is thought that for greater safety, they muffled their horses’ hooves and it is known they sometimes traveled by night.”) It is a fitting tribute to the miraculous young woman, who once said to a compatriot, in her imperious and divine way, “Tomorrow I shall have much to do, more than I ever had yet, and the blood will flow from my body above my breast.” Her courage and conviction, Sackville-West writes, were superhuman.

1984 by George Orwell

When I realized that much of this book has to do with the courtship of depleted bureaucrat Winston Smith by lively political dissident Julia, my interest in it greatly increased. 1984 features, perhaps, the most moving kind of love story–clumsy, innocent, fragile, and all too susceptible to corrosive external forces. This romance novel, of course, turns into a horror novel upon the capture of Winston by the double-dealing O’Brien, and the ghastly tortures, physical and psychological, which follow.

Leaving behind, for a moment, the cliched cultural shorthands which now surround this novel (“Big Brother,” the “four lights,” “Orwellian” as an adjective) it is an incredibly powerful work of art and a masterwork of craft. The last four words are calculated to break your heart.

Honorable mentions: The Secret History by Donna Tart, With Their Hearts in Their Boots by Jean-Pierre Martinet, Poems of Anna Akhmatova, Blubber by Judy Blume, The Devil is an Ass by Ben Jonson

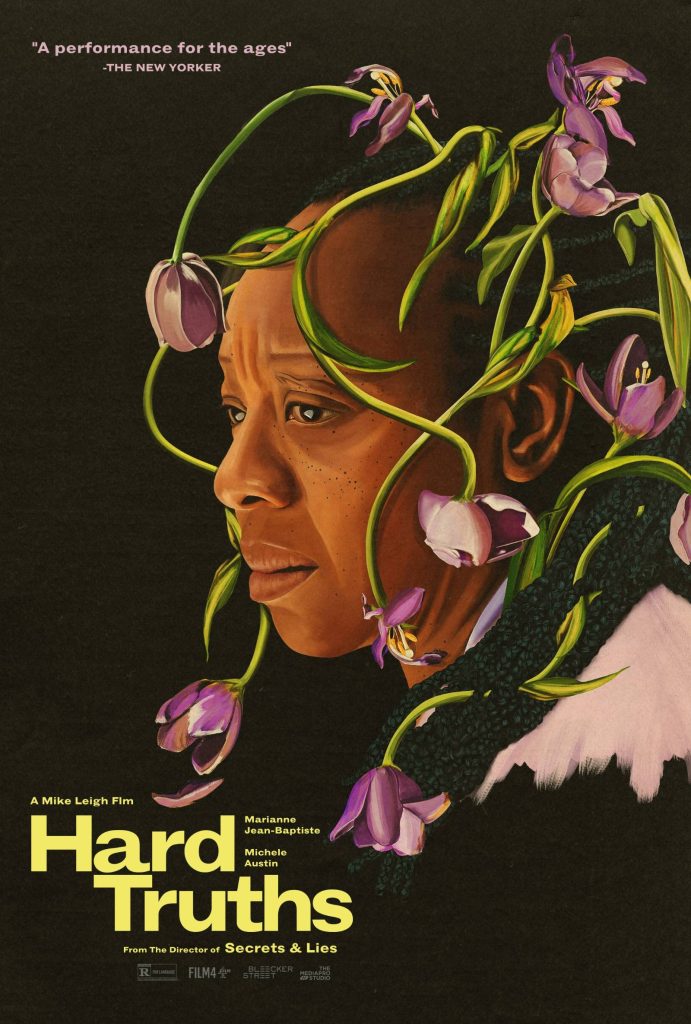

Hard Truths (dir. Mike Leigh, 2024)

In an ocean of incredible Mike Leigh characters and performances, Marianne Jean-Baptiste’s Pansy is one of the best. In one sense, she’s incredibly funny. There is a kind of zany, sketch comedy logic to her appearances onscreen: at what mundane thing will she get over-the-top pissed at at the grocery store? The dentist’s office? The furniture store?* But then, drip by drip, the wider view of her unhappy family is revealed, and we learn how she both traps them and is trapped by them. Her husband Curtley and her son Moses have all but given up on expressing feelings of domestic love, Curtley has overlooked Moses as an apprentice at his plumbing company (choosing the conspicuously similar Virgil instead), and, meanwhile, the forlorn Moses has lost all sense of his self-worth.

The glimpses of familial equilibrium we receive throughout the film (Moses has bought Pansy some Mother’s Day flowers; Pansy and her sister Chantal are able to have a real, unguarded conversation about their mother at her graveside) succinctly express that there’s room for change in this family, but that these sorts of things are never truly over. Don’t miss the one-scene character the end credits lovingly dub “Moses’s New Friend.”

*To quote Donna Tartt: “It was this unreality of character, this cartoonishness if you will, which was the secret of his appeal […] Like any great comedian, he colored his environment wherever he went; in order to marvel at his constancy you wanted to see him in all sorts of alien situations: Bunny riding a camel, Bunny babysitting, Bunny in space.” Pansy riding a camel, Pansy babysitting, Pansy in space.

Lawrence of Arabia (dir. David Lean, 1962)

It’s now difficult to imagine the producers of this film seeking to put Marlon Brando or Albert Finney under contract—Lawrence of Arabia would be a lesser film without the ethereal presence of Peter O’Toole. His timeless performance, alternatingly strong and weak, vicious and wounded, is silken and angelic, and possesses both the beauty and the fury of the angel.

This is to say nothing of his counterpart in black, Omar Sharif, as sleek and imposing as a cleaver. Lawrence of Arabia has the sweep and grandeur of classic Hollywood, but the smart, quiet, subtext-laden dialogue of midcentury British drama (thanks, in no small part, to the script by playwright Robert Bolt):

Sherif Ali: What is your name?

T.E. Lawrence: My name is for my friends. None of my friends are murderers.

Beau Travail (dir. Claire Denis, 1999)

Austere, lonely, and crystalline are the words for this pared-down reinvention of Melville’s homoerotic psychodrama Billy Budd. The astounding, ineffable final scene is one of the best in cinema.

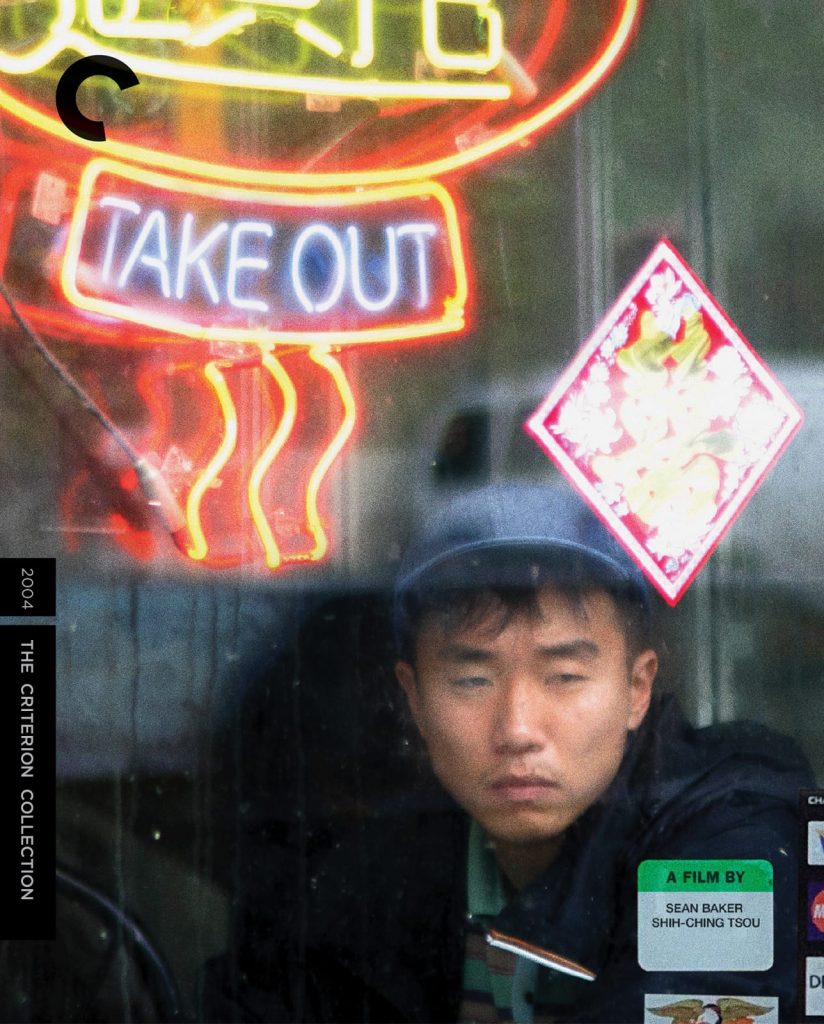

Take Out (dirs. Sean Baker & Shih-Ching Tsou, 2004)

This early Sean Baker film is a drum-tight and socially-conscious “race against time” story–on a budget of $3,000! The main cast, a mix of American performers, Asian performers, and real-life takeout workers, mesh together seamlessly. The supporting cast, a diverse array of authentic New Yorkers who were hired after responding to an ad on the Playbill website, lend a Safdie-before-Safdie verve. The terms of this movie are set up early and all it does afterwards is pay out like a slot machine.

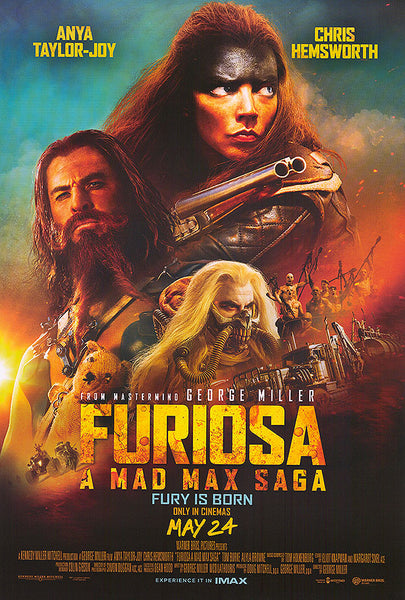

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (dir. George Miller, 2024)

The instinct to imagine the end of the world is an old and eternal human instinct, and after the mounting iniquities of the 20th century, the apocalypse seems only more and more prominent in our cultural imagination. After Dante, after the Dutch masters, after Ellison, Wells, McCarthy, and Romero, Miller is the living leader of this visionary tradition. Whether the oasis-cool Praetorian Jack knows it or not, he paraphrases Orwell as he sits dumbfounded and helplessly intones to Furiosa “we are the dead.”

Sloppy writing, plot holes, sure, Furiosa has some of that. In a world so scarred by violence against women, are we to believe that Furiosa, aging through the entirety of her puberty, perfectly concealed her gender with nothing but a head wrap and a face mask? Well, Rosalind similarly deceived the outlaws in the forest of Arden with nothing but a pair of hose. This is the tragic and consequential world of myth. Our rules do not apply.

Honorable mentions: The Last Days of Disco (dir. Whit Stillman, 1998), Fallen Angels (dir. Wong Kar-wai, 1995), Some Kind of Monster (dirs. Bruce Sinofsky and Joe Berlinger, 2004), The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, & Her Lover (dir. Peter Greenaway, 1989)

That’s all you’re getting out of me! See you soon!

Hated Lawrence of Arabia. Would have liked to see you write that play for the inmates but I understand. Maybe one day. Cheers to the beginning of your “real” life, and here’s to hoping that, one day, you’ll regard the “fake” life as vibrant and well-lived.

The fake life had a lot going for it, but the new one will have less poverty, confusion, and self-loathing. That’s worth a lot.