Evening, all.

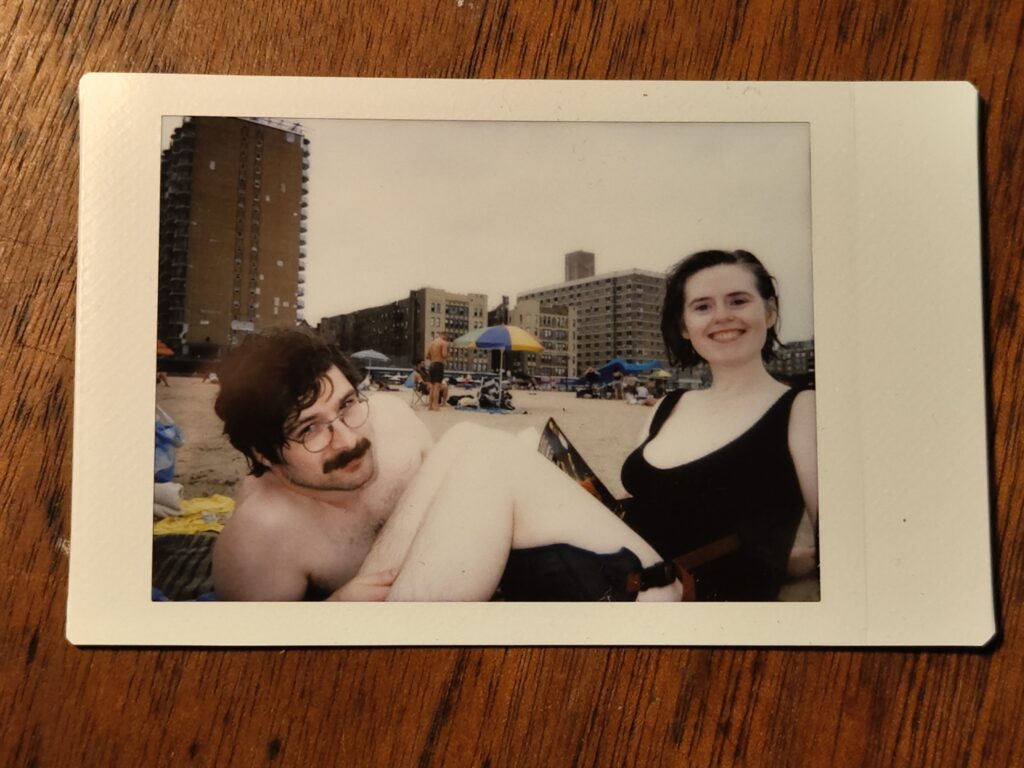

2025 presented a lot of opportunities to me. I had lots of at-bats as a director and performer (including my debut as an audiobook narrator), ginned up a couple short plays and stories with which I’m quite happy, and expanded my practice as an educator. Still, some of my happiest moments this year were spent in quiet, at study, with people I love. Those moments are reflected below.

By the way, check out the date of this blog post. Notice how it says December 30th, not January 31st? Yeah, I thought you’d appreciate that.

BOOKS

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Well, what do you know—turns out when you read a book widely considered a masterpiece, sometimes it ends up actually being a masterpiece.

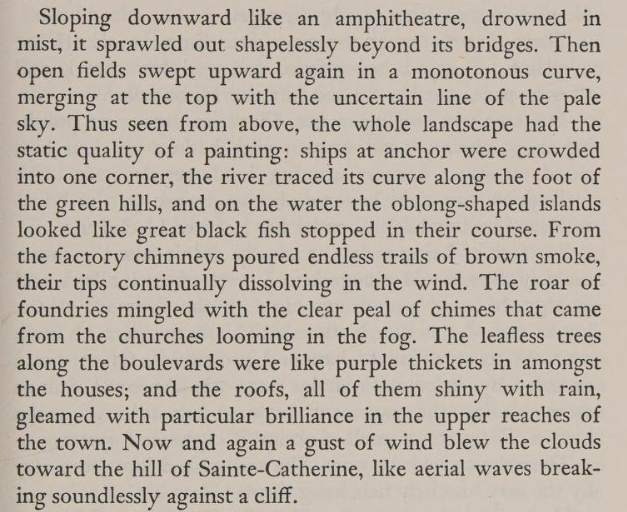

Much ink has been spent on describing Flaubert’s painstaking effort to perfect his writing on the sentence level, to create prose as “rhythmic as verse, precise as the language of the sciences, undulant, deep-voiced as a cello, tipped with flame,” a process which sometimes led him to spend an entire week working on a single page. And it’s tempting to dismiss this as mythology, a dog and pony show of self-torture that artists put on when they feel that their profession is not sufficiently harrowing, arduous, manly, etc. But then, you read a passage from Bovary like the one below (in which the title character sees the city of Rouen rising in the distance as her carriage crests a hill), and you think, well, this is incredible, and may well have taken a week to bring to life.

Madame Bovary is unforgettable. Her tragedy, and the saints, villains, and fools attendant to it—the pretentious, bloviating pharmacist Homais, the seductive rake Rodolph, the lovestruck, silent, and helpless young Justin—you will never forget it.

In Search of Theater by Eric Bentley

Bentley is best known as the critic who introduced Bertolt Brecht to the English-speaking world, but his yearbook of theatre goings-on in the late 1940s shows him at the very vanguard of drama both traditional and experimental, classical and current. In these highly literary essays, his tone is one of enthusiastic expertise, but also of dishiness and scandal—he consistently voices his contempt for Eugene O’Neill, dismisses Fry, Anouilh, and Giraudoux as whimsical fluff, and claims that Anthony Quinn was a better Stanley than Marlon Brando (!) Yet his reflections on the theatre never lose their sense of boyish excitement; he relishes the quashy, comfortable luxuries of London revival theatre, astounds at Jean-Louise Barrault’s masterful physical theatre in Paris, and sinks his teeth into directing an early production of The House of Bernarda Alba. One only wishes that this book could’ve extended into the 1950s, so that we could hear Bentley’s off-the-cuff observations on Beckett, Behan, and Genet.

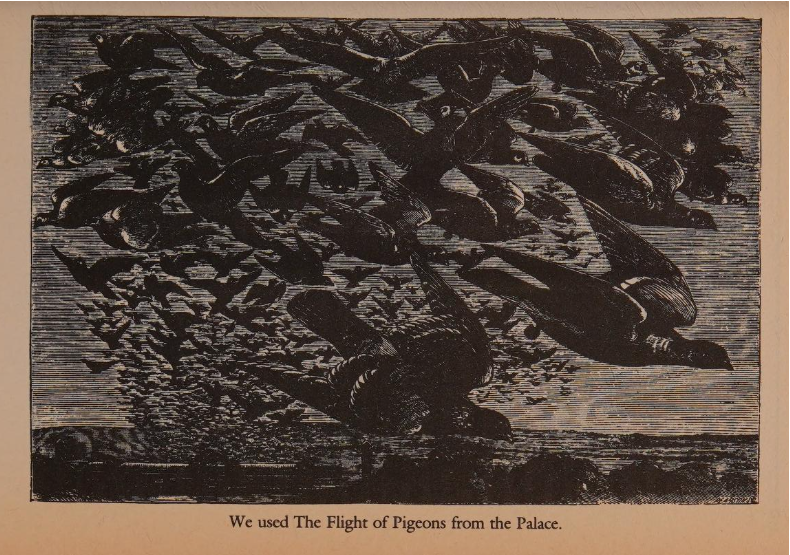

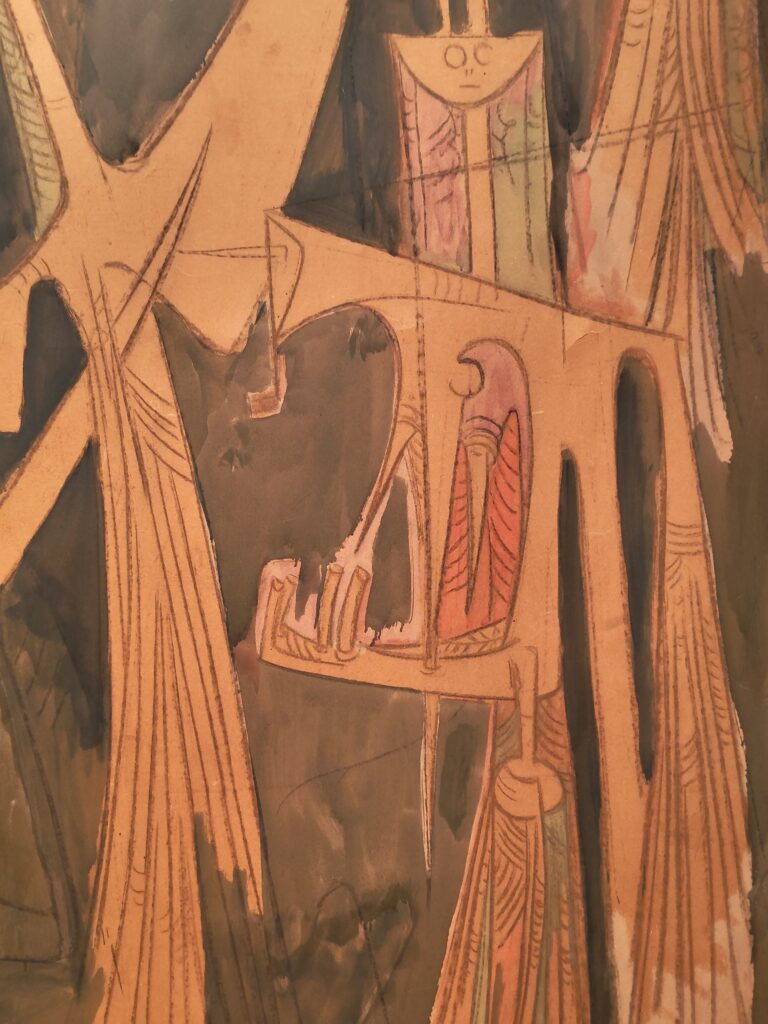

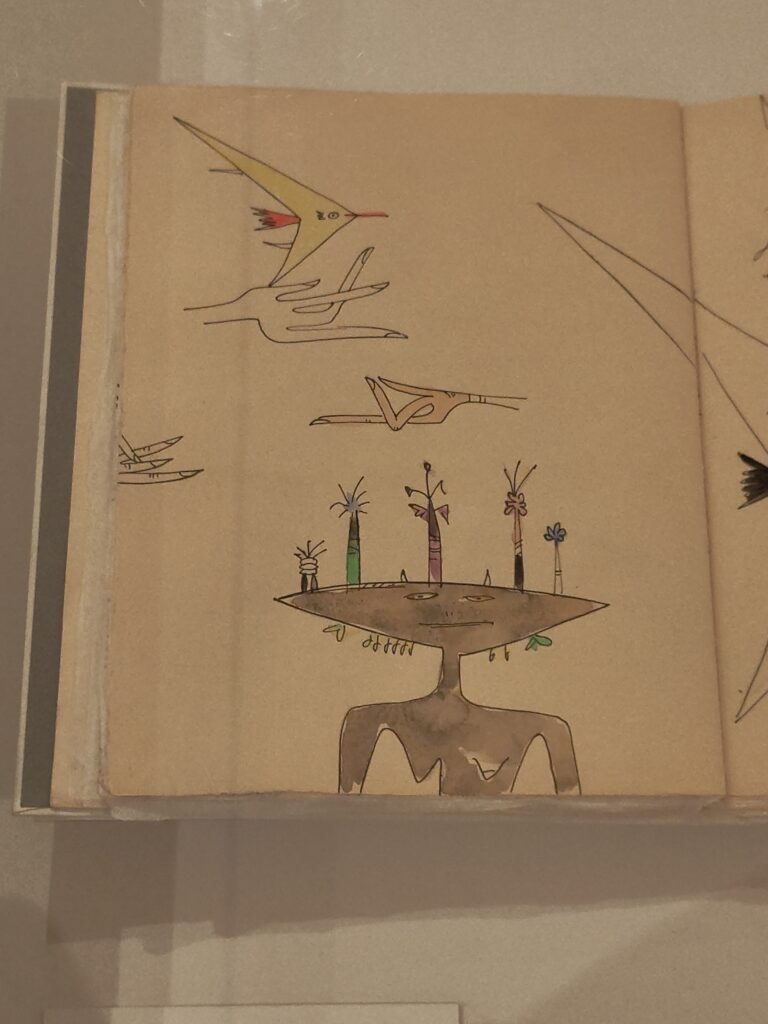

40 Stories by Donald Barthelme

Donald Barthelme wrote stories that sampled and metastasized nearly every impulse of mid-20th century postmodern fiction, from Beckett’s experiments with form, to Pynchon’s mocking humor, to Carter’s acts of radical adaptation. 40 Stories in particular shows Barthelme’s talent as a collage artist; he has illustrated “The Tolstoy Museum” and “The Flight of Pigeons from the Palace” himself, with a surrealism and dark beauty that evokes the work of Max Ernst.

Spend enough time around the MFA set and you’ll find that many of them count Barthelme as an influence. It’s easy to see why. Barthelme’s stories are as breezy and witty as a sketch in the New Yorker, yet as rewardingly brain-teasing as anything on the Nobel shortlist.

The King in Yellow & In Search of the Unknown by Robert W. Chambers

Chambers is best known as an important proto-Lovecraftian, and while stories from The King in Yellow like “The Repairer of Reputations” and “The Yellow Sign” are effectively queasy, his connection to Lovecraft precedes him and tends to obscure how inventive and heterogenous a writer he really was. “The Demoiselle d’Ys” is a fantasy romance as simple as it is elegant, and the prose poems of “The Prophets’ Paradise” indicate a strong French Decadent influence. Then, with In Search of the Unknown, he treats us to something really special—a novel-in-stories about a paranormal biologist tasked with developing the cryptozoological wing of Bronx Park, a real-life civic project brand-new at the time of the book’ 1904 release, and which now hosts the New York Botanical Garden and the Bronx Zoo. In Search of the Unknown trots along at a winsome, episodic pace, and as you wingman the biologist in his encounters with strange beasts and strange people, you’ll find yourself in the thick of a forgotten classic of turn-of-the-century genre fiction that combines humor, adventure, science-fiction, and romance with ease and grace.

“Long after the blue-and-black victoria had whirled away down the crowded quay I stood looking after it, mazed in the web of that ancient enchantment whose spell fell over the first man in Eden, and whose sorcery shall not fail till the last man returns his soul.”

The Road to Oz by L. Frank Baum

After having put out a few Oz novels, Baum was sick of having to write them (“It’s no use; no use at all,” he writes in the introduction to 1908s’s Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, “The children won’t let me stop telling tales of the Land of Oz.”) However, he trudged on, and it was in 1909’s The Road to Oz that he found the way to do so: he was clearly immensely inspired by the Shaggy Man, his rather sweet rendition of the quintessentially American figure of the bum. If this rather uneventful book has any narrative thrust at all, it is the Shaggy Man’s journey from aimless, homeless, and unloved, to purposeful, welcomed, and admired. On his way there, we see him we see him in moments of great vulnerability, feeling that he needs to lie in order to be accepted, feeling unworthy of the gifts and hospitality of others, and feeling ill at ease in places of comfort and luxury. The world has taught the Shaggy Man that he isn’t good enough for good things. Oz teaches him that he is, because everyone is.

Honorable mentions: Molloy by Samuel Beckett, Confessions of a Young Novelist by Umberto Eco, After Delores by Sarah Schulman, The Nonexistent Knight by Italo Calvino, The Torture Garden by Octave Mirbeau

ALBUMS

Frog – 1000 Variations on the Same Song (2025) / Count Bateman (2019)

Frog! Frog! Frog! The gentle, lofi songs of this folk rock band from New Rochelle were my soundtrack to 2025, and it’s no contest. Julia and I were sitting in my apartment listening to WFMU this past February when we heard our first Frog song, their New York twist on the classic Irish anti-war song “Arthur McBride.” We dove deep into the catalogue, finding that their trove of love songs offered us many meaningful candidates for “our song,” though “It’s Something I Do” likely takes the title in the end.

Akiko Yano – いろはにこんぺいとう [The Color is Konpeito] (1977) / ごはんができたよ [Dinner is Ready] (1980)

Calling Akiko Yano “the Japanese Kate Bush” is now so commonplace as to be a cliche, but hey, people do it for a reason. Her incredible vocal range, her compositional virtuosity, and her mastery of many genres new and old do seem to indicate that she and Bush are fruit fallen off the same tree. However, as is often the case in comparisons of this kind, the argument could easily be reversed, and Bush could very appropriately be called the English Akiko Yano. “Wuthering Heights,” Bush’s first single (stop and consider that for a minute), was released in 1978 when Yano was already two albums deep, having come out with vibrant art pop singles like “Denwa-sen” and “Ike Yanagita.” In 1980, Bush was still putting out early singles like “Babooshka,” whereas Yano, having already moved through her jazz fusion, folk pop, and piano rock eras, was reinventing herself once again with uber-contemporary synthpop single “TONG POO.”

…woof, that felt wrong. Let’s just be grateful we have both of them.

Gene Clark – No Other (1974)

David Geffen, whose name I cannot escape whether I’m in my ancestral New Haven or my beloved New York, signed Byrds songwriter Gene Clark to a solo career in the early 70s. The warm, spiritual, and expansive No Other was the result. It was a masterpiece, and Geffen hated it. He declaimed it as ponderous experimentalism, an expensive boondoggle of eight rather long and precocious songs. To hear it from Geffen, No Other was fanciful hippie nonsense so unsalable it may as well have been Trout Mask Replica. How close-minded he was! No Other is lush and exquisite, Clark’s resonant tenor voice cracked and emotional as it soars over a glimmering ocean of country, rock, soul, and dark-tinged psychedelia. And although the album is at times riddling and arcane (the sexy and deep title track seems, in part, to be a paean to something or someone Clark calls “the god of love), it is felt bone-deep. Several important people rejected No Other at the time of its inception, while others, to borrow a line from album opener “Life’s Greatest Fool,” looked “into the darkness of the day.”

Katie Gately – Fawn / Brute (2023)

I once said to a friend that I’d hate to meet Katie Gately’s ominous musique concrete debut EP in a dark alley. It’s for that reason that her name came to mind when I was tasked with contributing a song to Halley Freger’s music listening party (theme: scary). Little did I know that, while I wasn’t looking, Gately had developed an entire second career as a pop composer and vocalist! Fawn / Brute’s complex, many-layered soundscapes bely Gately’s background as a sound designer, but that doesn’t mean that Fawn / Brute is overly brainy. No one could mistake “Tame” for academic insiderism as it unleashes a squelching, jazzy house breakdown that could go head to head with the best of St. Vincent and Lady Gaga.

dj galen – the Death of Music (2025)

Before this year I was familiar with Galen Tipton from her ASMR-influenced sound collage albums and her collaborations with vaporwave group Death’s Dynamic Shroud. I always liked her, but never was crazy about her. That changed with the Death of Music, her eerie, infectious mix of hyperpop and old school house released alongside a series of eyepopping, thematically linked Photoshop paintings (onesuch above). In the paintings, flesh is bountiful and disposable. It pops and tears and stretches until it’s no longer faces we’re looking at, just red meat and bloody ligaments and ghoulish faces floating hallucinogenically over an opalescent sky. Tipton does something similar with the sampled voices that make up the majority of the album’s melodic hooks; they are chopped and shrunk and cloned and sped up and slowed down, seeming like voices in certain superficial ways, but no longer serving any of the traditional functions of the voice. Death and degradations of the body run through this album like sticky blood coursing through a vein, and from death’s fecundity comes springy, spongy, damp and villainous music. Galen Tipton has rechristened herself dj galen.

Honorable mentions: Wang Lei – 美丽城 [Belleville] (2003), Van Morrison – Saint Dominic’s Preview (1972), Skepticism – Stormcrowfleet (1995), Cinema Strange – The Astonished Eyes of Evening (2002)

MOVIES

Central Park / Zoo / Belfast, Maine (dir. Frederick Wiseman, 1990, 1993, 1999)

A memory I will likely hold onto for the rest of my life is of getting off work in the early spring of this year, walking ten minutes over to Lincoln Center, and sinking into a seat to enjoy whatever was on offer in their career retrospective of documentarian Frederick Wiseman. When, in appreciations of cinema, one uses words like “epic” and “immersive,” one is often praising the painterly auteurism of a Malick or a Tarkovsky, or, alternatively, the pulp magazine creations of Jackson, Cameron, or DeMille. Yet few filmmakers transport us to states of studious and enraptured wonder so reliably as does Wiseman.

His multi-hour, large-scale features are sometimes called “minimally-edited,” though this is an (understandable) error. Uninterrupted takes of up to and over 10 minutes may feel unedited until one begins to appreciate Wiseman’s trademark juxtapositions, which reveal a poet’s sense of metaphor and irony. In Belfast, Maine, who else but a great poet would think to cut from a rehearsal of Death of a Salesman, in which an actor rages against the coming of a cruel, indifferent future, to a brutal scene of a hunter approaching a wolf caught in a trap, coolly retrieving his gun, and shooting point blank? Who else but a great philosopher would match moonlit footage of zoologists observing a rhinoceros calf being stillborn to footage from the next day of the same stillborn being disemboweled by the same zoologists under a merciless midday sun?

Chilly Scenes of Winter (dir. Joan Micklin Silver, 1979)

With her cast of cute young professionals, her dialogue as fluid as music, and her skittering tales of life in New York, Joan Micklin Silver makes room for herself on the shelf next to Woody Allen, Elaine May, Nora Ephron, and Nicole Holofcener. These are associations of subject matter, not of chronology or quality; I’m not convinced that Silver is secondary to any of her more well-known cohort. Her mastery of the romcom format can be seen in great movies like Between the Lines and Crossing Delancey, but her fantastic interruption of the format is Chilly Scenes of Winter.

We are, in effect, trapped in Charles Richardson’s mind. He loves Lauren Connelly, and was justified, once, but their relationship has long been over. Speaking directly to the camera, Charles welcomes us along as he waits outside his Lauren’s home, contemplates suicide, and, in the middle of a pleading argument with Lauren, makes a misplaced and curiously hollow threat of rape. That Charles never explodes into violence is telling of the strange character of this film. His undeniable psychic instability is not Silver’s focus as much as is his long journey down from being in love. This is no thriller and no cautionary tale. Charles is nuts, but perhaps about as nuts as any of us watching who have been made temporarily insane by heartbreak.

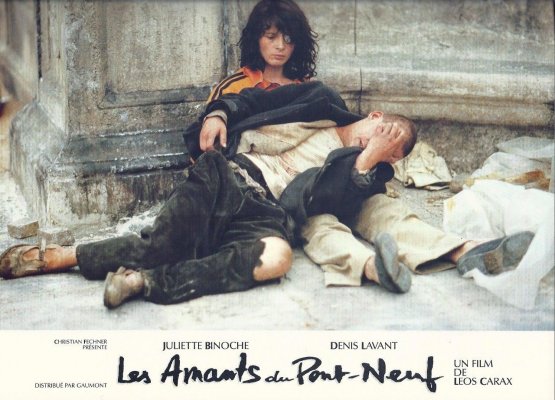

The Lovers on the Bridge (dir. Leos Carax, 1991)

This is surely the most French film I saw all year. It is about the relationship of a bohemian runaway slowly going blind with a firebreathing, acrobatic circus performer, both homeless, and glamorously homeless. They make Paris theirs, especially the dilapidated Pont Neuf bridge, in its stonework crenellations looking very much like medieval battlements upon a neoclassical stage—the perfect place for this couple to play out the vulnerable, fiery, and passionate drama of their love. It is no coincidence that the final shot echoes L’Atalante, another quintessential love story of the French cinema. This is a movie about Capital L Love, in all its bombast and squalor and grandeur.

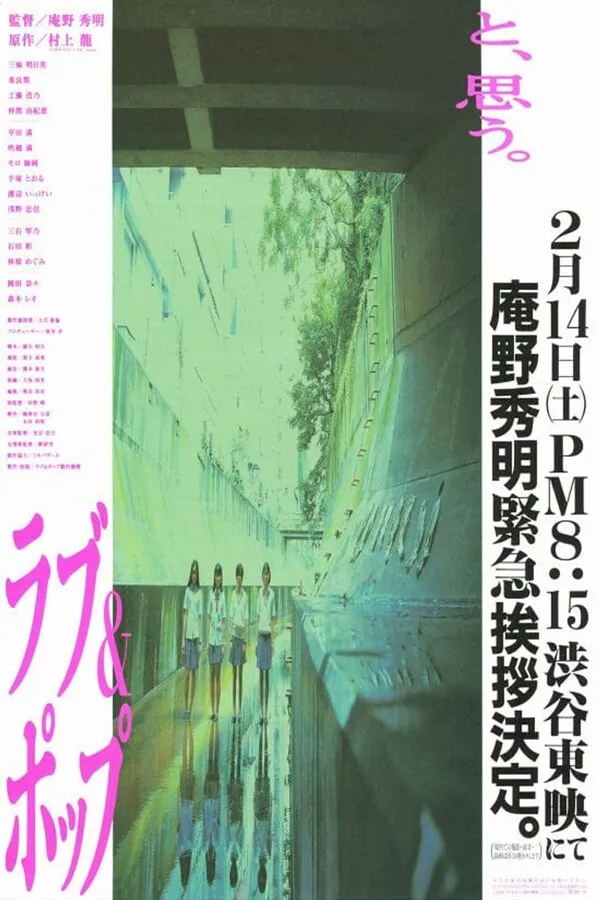

Love & Pop (dir. Hideaki Anno, 1998)

Briefly after having wrapped three years of work on Evangelion (!), Hideaki Anno set to work on Love & Pop, a film which, like Evangelion, explores the perils and potentials of being a city kid in the 1990s. In Evangelion, the panel of government scientists lording over Shinji and friends are a powerful metaphor for the fleets of parents, teachers, and professionals who afflict the young with their own ambitions and anxieties, but in Love & Pop, Hiromi and her friends are on their own. Their escapades in Shibuya malls, streets, and suburbs are captured with consumer-grade digital camcorders, giving the early scenes a feeling of friendly intimacy and presentness. But as soon as they hatch the idea that they could earn some spending money by charging misfit male urbanites for first date experiences, the blurry, bleary cinematography which once seemed so welcoming suddenly feels sticky and illicit. Hiromi’s seedy, resilient coming-of-age becomes the film’s main concern, as do the vivid character sketches of the loners she meets along the way. All is depicted with impressive realism, and empathy for girls and weirdos alike.

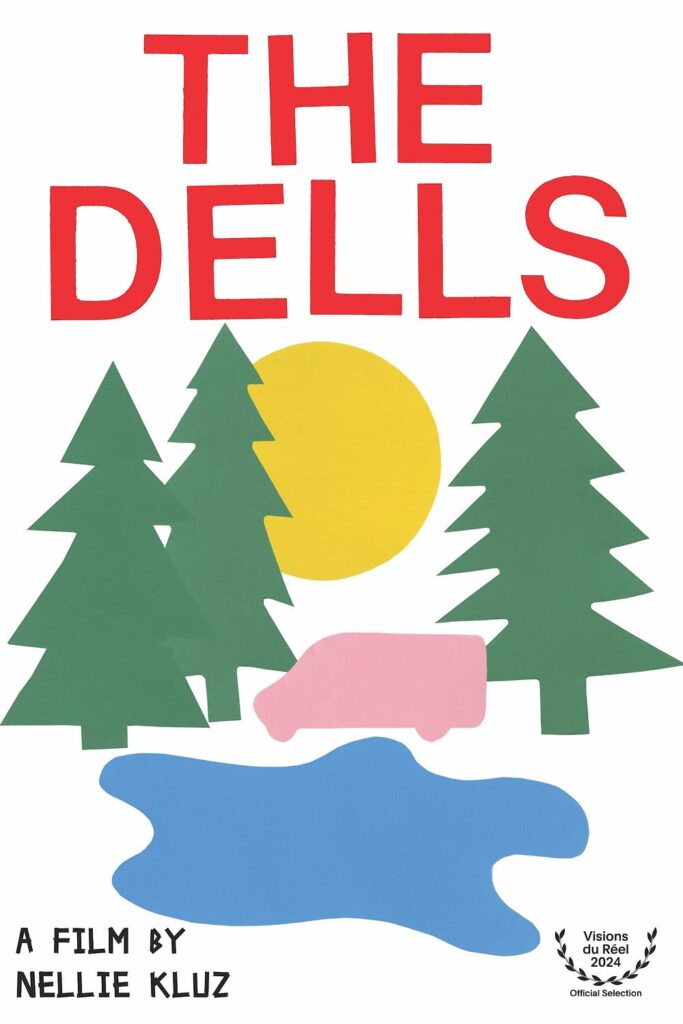

The Dells (dir. Nellie Kluz, 2024)

Imagine my pleasure: a gorgeous spring day, a ride on the ferry to Rockaway Beach (with marzipan snacks on the top deck), and a front seat to The Dells at the wonderful outdoor Arverne Cinema, ocean air all around me.

The Dells captures a small but lively subculture in the resort town of Wisconsin Dells—that of visa workers, mostly young and mostly European, who have traveled to this tiny Midwest facsimile of summer fun to work as waiters, shop assistants, and in other grueling service industry roles. They, of course, are not the ones having the aforementioned summer fun—they are paid poverty wages, sometimes struggle to find a place to live, and are subject to the attentions of predacious locals who correctly identify them as clueless, friendless, aimless, and young. In these summer jobbers there’s a mirror image of ourselves: sort of having fun, but also very much sort of not, despite our attempts to convince ourselves otherwise.

Honorable mentions: 28 Years Later (dir. Danny Boyle, 2025), Bugonia (dir. Yorgos Lanthimos, 2025), Oliver! (dir. Carol Reed, 1968), Before Sunset (dir. Richard Linklater, 2004), Dad & Step-Dad (dir. Tynan DeLong, 2023), Possibly in Michigan (dir. Cecelia Condit, 1983)

ALSO…

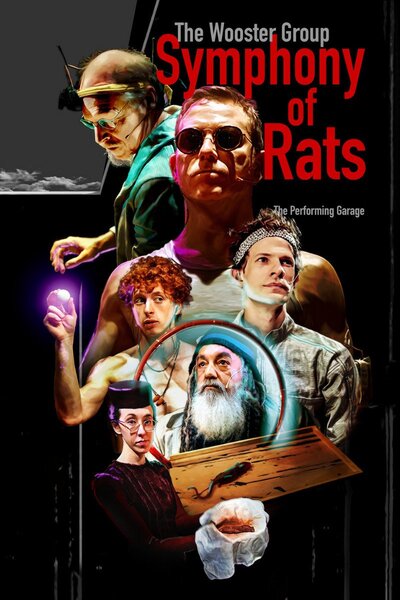

The Wooster Group’s Symphony of Rats at The Performing Garage

My 2025 was full of theatre, but this revival of Richard Foreman’s 1988 play Symphony of Rats was the best of it. High-tech, playful, dadaist, and often downright creepy, it was the wonderful reminder I (and perhaps you too) needed that theatre can be exactly as free associative and delightfully unexpected as our imaginations allow it to be.

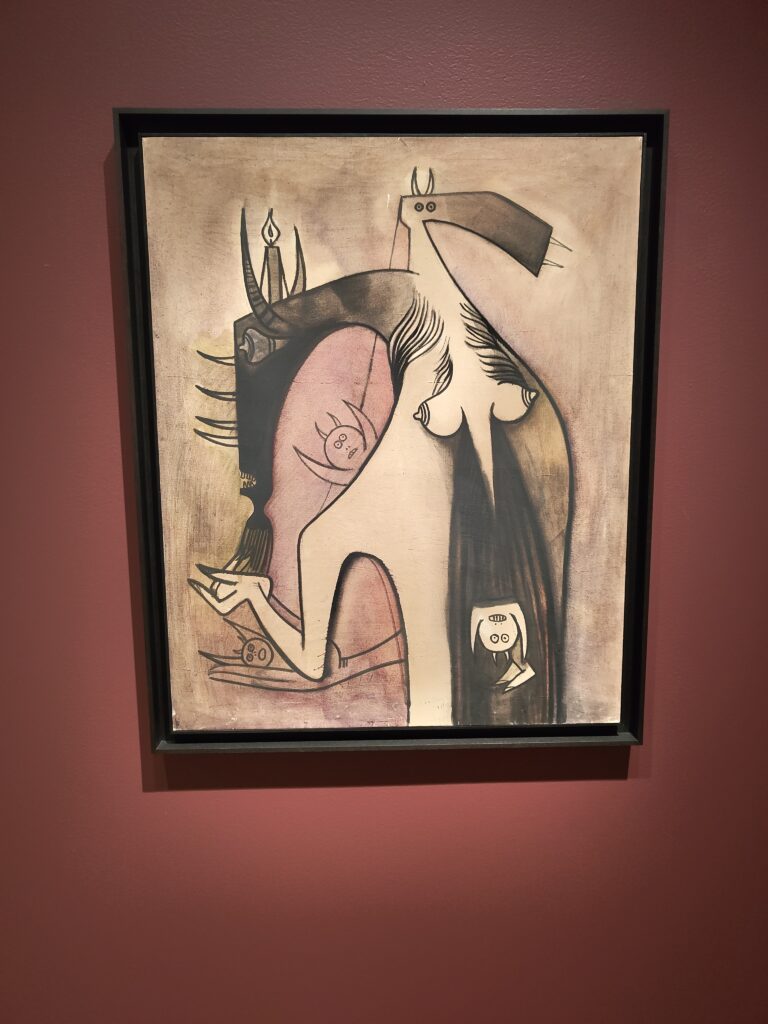

“Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” at MoMA

Decades of Cuban surrealist Wifredo Lam’s explorations in areas both stylistic and personal are given full breadth in this expansive exhibition. Of special interest are his collaborations with poets Aimé Césaire and René Char. It’s still on for a few more months. Check it out!

More of my art writing:

Samuel Beckett’s “Play” (dir. Anthony Mingella, 2000)

Samuel Beckett by Al Alvarez

“Vera, Or, The Nihilists” by Oscar Wilde

“Caesar Antichrist” by Alfred Jarry

“Freshwater: A Comedy” by Virginia Woolf

“She Stoops to Conquer” by Oliver Goldsmith

The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gentleman by Washington Irving

Lamb to the Slaughter by Roald Dahl

Love Me Tender by Constance Debré

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed by Harlan Ellison

Confessions of a Young Novelist by Umberto Eco

That’ll be all. These EOY posts of mine get longer and more elaborate every year. Maybe we’ll downsize next time, but in the meantime I hope you liked this one.

I’ll see you down that old, dusty road.

—Matthew.